Click here to choose to play Music Selections from

"An Evening of Elizabethan Music" by The Julian Bream Consort

RCA Victor LP 2656 (c. 1965)

(music takes 30-60 seconds to load)

Why the Shakespeare Name Endured

SECTION I First of all, Shakspere was a good thing to De Vere. Anthony Munday and John Lyly had covered for him since his return from Europe as a playwright, and after Lyly turned out a spy for William Cecil Lord Burghley in 1592, he needed a new front. Lyly never produced another play after he left De Vere. Although patronage was acceptable, being known to do the work of the rabble wasn't. It was more than declasse, it was shaming and dangerous. Censorship reigned as a fact of life. De Vere all but flouted the taboo. His mansion Fisher's Folly became a small university for playwrights. Cecil described the associates there as "lewd persons". De Vere's political views, easily inferred from baleful plays about the aristocracy, also provoked Cecil's reactionary fears. Shakspere fit the personality type necessary as a front man. He was illiterate and wouldn't compete, a showman canny to the roles a front assumed–the airs, the brags, the magnanimous pose. He proved basically honest when it came to agreements and contracts. De Vere expressed this opinion when Shakespere capriciously went beyond his function and London writers castigated him: "He is honest in his business dealings." The criticisms stopped. If he made trouble, De Vere could handle him. 'As You Like It' illustrates that. Fortuitously his name and De Vere's nickname were allonyms. De Vere needed a 'beard' and money to continue public theater. The latter dilemma got him the nickname "Pierce (for spear) Penniless". Withal, the guild knew and admired him. It was not satire to call him "Gentle Master William". He was genteel. He did lower himself to gentleman, i.e., Master, though the most noble of the aristocracy. From being in William Cecil's household, he became his foster-father's eponymous "William", a paternalism of the class. That he had been called spear shaker (hasti vibrans) since childhood, and that this association became further strengthened by his tourney exploits and Gabriel Harvey's rhetoric, ("Thine eyes flash fire. Thy countenance shakes spears"), cumulatively created the perfect match with Shakspere. The hyphen in his pseudonym Shake-speare gave away its contrived nature. Insiders would know the double-game. The public did not. De Vere played on his alter-names in several ways. His phrase, "Will he nill he?" had the subtext "Is he determined to go ahead or will he negate himself?", a formulation first expressed in his introduction to Bedingfield's translation of 'Cardanus Comforte'. He had said Bedingfield would murder philosophy, an integral part of human substance, if he didn't share his work. Obviously De Vere was determined not to 'murder' his own work, although how he would finally reach acceptable recognition remained unclear. The title of a tale he wrote in the 1590's, "Willobie and Avisa" asserts imperatively he would "be"–Will, O Be!–i.e., declare himself writer of his own plays, Avisa ('permission') standing nearby to sanction just that. The title isn't far away from his existential line, "To be or not to be, that is the question." Actively be or you aren't. Nashe referred to De Vere with the undercover sobriquet "Monox", alluding to the French 'my' and 'ox', short for Oxford. The picaresque "Pasquill Cavaliero" appears to be another alias, this time referencing his cavalier manner of life and the prospect that, given all the trouble with the Vavasour clan, he might give up and emigrate to Spain. The first name plays on the French negative, pas, to say, "No quill Cavaliero". In other words, HE's not the writer...

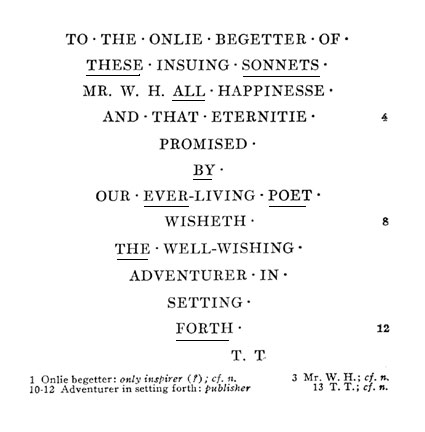

His plays were big business around London. In 1586 Elizabeth had granted him £1000 a year so that 'Princes may maintain their creations', in modern language keep the play work going, boost the national consciousness, and avoid financial ruin. By 1597, when Shakspere importunately stepped too far into his master's shoes, he became a laughingstock and had to be curbed. The 3rd Earl of Southampton, Henry Wriothesley, De Vere's son, paid Shakspere £1000 to cease his pretensions and just market his name for commercial use. This was the first time De Vere got his plays into print under the nom de plume Shake-speare. Shakspere used the money to buy a fine house back home and set himself up, including a crest. At that moment, in 1598, Cecil died and his son Robert became Chief Minister for Elizabeth. 'Robin' had grown up with, though years younger than, De Vere. He did not tolerate De Vere's Bohemian freedom, not because of religious or aristocrat's ethics but because he wanted no trouble of any kind and De Vere's later plays threatened that. 'Julius Caesar', 'Antony and Cleopatra', 'Richard II'–were not light drama. They spoke of overthrow, intrigue, and cynical realpolitik. De Vere was a strict monarchist. Nevertheless his plays examined politics realistically, revealing the conflicts within his class, a consummation Cecil devoutly did not wish. Cecil simply kept the names De Vere or Oxford as far as possible from the plays, regardless that Englishmen in the thousands and ten thousands saw them at nightfall, cued by Protestant vesper bells. His minions made the author's own name-deception the means to subvert him. De Vere's and 'Shake-speare's names started appearing in publications simultaneously as two different people. The effect was to separate the aristocrat, and his class, from the dangerous 'Shake-speare', even though 'they' were one man employing a pseudonym and a stooge. It became inevitable De Vere's identity, no matter he was the literary giant of the age, would be buried for political purposes, to dissociate his personage from the controversial ideas, as well as for aristocratic solidarity, to bar other nobles from crossing class lines. Both strategies succeeded and neutralized the playwright. Neither at the time nor in future decades did the public detect the truth, that a rebel prince wrote Shake-speare. Their attitude remained politically docile. Consequently while the Essex Rebellion happened in 1601 with the Earls of Essex and Southampton in the lead, it didn't spread. Play-goers may have been fascinated with the world of their masters. That didn't mean they would overthrow them. Devereaux and Wriothesley seemed to think the crowd would march from the denouement of 'Richard II' at the theater to storm the Queen's gate. The actor John Wilkes Booth carried the theatrical-versus-prudential delusion one step further. The Essex principals soon surrendered; several were shot, more imprisoned and executed; Robert Devereaux lost his head and Wriothesley his freedom. Could he have become Henry IX simply by royal blood? Henry Fitzroy, Henry VIII's illegitimate son, wasn't his father's uncontested heir. Royal blood, like a noble's rightful claim to his art, did not move countervailing power. De Vere played no part in the attempted coup. Old, sick, lame, the wars were over for him. The Essex Rebellion remains in memory a political abortion, 300 marchers in an unruly band, the Elizabethan equivalent of the Russian Revolution of 1825 and precursor to the Revolution of 1688. Lady Pembroke, De Vere' in-law, via his daughter Susan, had her own dramatist front man, John Webster the carriage-maker's son. She suffered no inconvenience with the authorities. De Vere did and proved vulnerable to the State. Their taking his son hostage broke his heart. The Sonnets tell that story. He agreed to political quiescence. The status quo demanded his never emerging as author of the plays. That possibility got snuffed in the ensuing political repression, extending past the lifetimes of any involved with De Vere. Unrecorded or couched in code, any connections between the man and his artistic history dimmed year by year. The Cecils kept only the letters favorable to them. Robert Cecil took care to buy up De Vere's play companies and incorporate them into the court theater. The players recognized the best course, silence about De Vere. Cecil's final move was to suppress 'The Sonnets' after Wriothesley had gotten the book into print in 1609. Again, knowledgeable chatter among the elite or intelligentsia did not equal insurrection. The name-deception once advantageous to De Vere became de facto political doctrine in Jacobean England. Only by encryption could the true author be communicated: hidden in the dedication are the words, "These Sonnets All By Ever The Forth", i.e., De Vere and "deVierde" in Dutch being near homonyms.

Mr. D.L. Roper of Great Britain has gone further into decoding the Sonnets Dedication and the Stratford Monument than any other scholar to date. This is an area of the authorship question not subject to academic rhetoric and rank-pulling. It is factual. If anyone can demonstrate beyond reasonable doubt that these oddly worded artifacts can be tied in motive and form to Edward De Vere, the issue of 'Shakespeare's' identity concludes right there. Roper did that, relying upon the decryption suggestions of Dr. John Rollett. See the article SHAKE~SPEARES SONNETS, Thomas Thorpe's Enigmatic Epigraph Explained, linked here by Roper's permission. Had

the political atmosphere grown more expansive, De Vere might have

gotten due recognition politically and culturally. It was not to

be that the consummate artist of his time cracked through its aristocratic

Calvinist shell. Therefore the front, Shakspere, enjoyed not a decade

but centuries of counterfeit fame. SECTION III The

power of the new king changed little. Upon ascending to power,

James I honored De Vere ("The Great Oxford")

by releasing his son. He knew De Vere was no more a political threat

than Plato

had been. And De Vere, a closeted Catholic, had argued to spare James's

mother, Mary Stuart, in 1586. James I also favored De Vere's youngest

daughter Susan, a vivacious talented actress at court. After De Vere

died, a year later in 1605, James ordered seven 'Shakespeare' plays

performed for royalty. No other English writer had been honored

to that degree

and no noble. The Essex Rebellion remained in James' memory. The

night of De Vere's death, St. John's Day 1604, James I clapped Wriothesley

in the Tower, probably to warn him there must be no mischief now.

The never Henry IX walked out next morning. To

further establish the fiction and thereby ensure the publication

of the Folios in 1623, the De Vere clan propped

up now deceased Gulielmus

Shakspere's status. Jonson's recognizable verse appears on his Stratford

Monument. The tribute encrypts in its cross-word puzzle graphic structure

a vertical message: De Vere "is" the author, just as he "is" Shakespeare.

I wish to comment about a section of the Stratford Monument Mr. Roper did not discuss. The Latin dedication placed above Jonson's English dedication on the plaque is as important as the odd phrase which reads 'Quick Nature Dide' in the English dedication. [Mr. Roper has since amplified his discussion of the Latin phrase. See the above website link.] Let us first discuss the 'Quick Nature Dide' wording. In English and so placed, the phrase is all but meaningless. Why was it there at all? To further identify De Vere on a monument to 'Shakspeare'. The phrase owes its secret value to the original Latin (Summa Velocium Rerum), from which Jonson takes the first syllable of each Latin word to make 'Sum VeRe' [I-am Vere] out of the complete phrase. He redundantly embeds his secret about De Vere as the true Shakespeare, in case he hadn't already put across the point or someone claimed co-incidence in the Cardano Grille. He both conceals and furthers his purpose with the English translation of the Latin. For only a fluent Latin speaker would see that the English phrase jogs one's memory of the original Latin. 'Quick Nature Dide' via the Latin equivalent leads to De Vere's constructed name: 'Sum VeRe'='I-am VeRe'. All this is decodified in Roper's tract. But

the Latin sentence preceding the English dedication on the plaque

is explicit, unambiguous, elevated praise of a noble

soul. Here Jonson

does not prevaricate. The saying is "Judicio pylium, genio Socratem,

arte Maronem. Terra tegit, populus maret, Olympus habet". This

amounts to: "In judgment a Nestor, in genius a Socrates, in

art a Virgil [whom] the earth

buries, the people revere, the gods regard". For those who knew

De Vere,

it was appropriate language. For those unaware of the monument subterfuge,

it was Latin that must make sense, i.e., was taken on faith. For

those who

both knew Shakspere, the claimed subject, to their knowledge a grain

merchant and litigious bully, AND Latin, it must have been curious

testimony in the extreme. The subterfuge comprised of literary Latin and cryptographed English on a monument in rural Warwickshire succeeded. The Folios were published without incident. The truth for the ages survived, though concealed in code and obscured by myth. That mythology was never local however. No legends of the Bard abounded in Stratford after Shakspere died, nothing akin to the tales following Samuel Clemens in Hannibal, Missouri decades after he left. Rather, the Warwickshire country folk spoke of "The Swan of Avon" who lived upriver at Bilton and "The Shakespeare Room" where 'As You Like It' was written. Jonson referred to 'the Sweet Swan of Avon'. It occurs to me the swan is graceful, serene in his element, but awkward and helpless on land, a good metaphor of the poet's life. SECTION IV Politically, regionally, intellectually, the official truth triumphed: a hapless unknown yeoman walked off his dusty street into the fortifications of unassailable 'genius'. De Vere's descendants could not fight that momentum. They needed to survive socially and financially as the following centuries extolled Romantic individuality, heroic genius, Hegelian glory. They kept mum publically but nevertheless maintained remnants of the Oxford prodigal son. In the October 1991 Atlantic Monthly is recorded Sotheby's 1948 sale from De Vere's great-granddaughter's estate: Holinshed's 1587 'Chronicles'; 'The Noble Arte of Venerie or Hunting' (1575); Castiglione's 'Il Cortegiano' (1563), an Italian edition which De Vere sponsored to be translated into Latin; Hakluyt's 'Voyages'; and a copy–signed in the hand of Henry Wriothesley–of the Amyot 'Lives' of Plutarch. These were precisely the books, published in his–their–era, Edward De Vere would have had in his library. Somehow the family kept them together for 350 years.

They kept his portraits for a time, including one–the Ashbourne–that was later altered to 'Shakespeare' in the late 1700's, two hundred years after the sitting. It was the right image, the right moniker, but no longer the right identity. Perhaps ancestral respect lived on in protecting the Oxford background. But provenance hoaxes were bound to follow in the wake of officially falsified doctrine. That required any De Vere portrait to vaguely resemble the Droeshaut etching on the 1623 Folio, a cartoon by a youth who had never seen either man. There must have some vestigial memory of who the real author was, else his portrait wouldn't have been a candidate to obtain and change. The Boar's-head insignia got painted over, the combined De Vere-Trentham crests misrepresented, widow's-peaks disappeared in favor of receding hairlines, and thick eyebrows thinned. Distant facts did not matter. In the 1790's John Adams visited Stratford On Avon doubting it could have produced Shakespeare. When P.T. Barnum went there in 1847 he wasn't interested in certainty, only amusement potential. He sought the fanciest house in town to market as Shakespeare's. The townspeople objected and defiantly made the second biggest "his" birthplace, in order to keep profits local. Since then, a noted few have questioned the myth: Emerson, Whitman, Freud, Galsworthy, James, Chaplin, Welles, Gielgud, Jacobi, and those, mainly American, scholars working at their own expense to reach a credible answer. Like other unstable belief systems, the Shakespeare establishment forbade apostasy. Academia obeyed that policy. I like to think that the authorship truth which the unheralded scholars sought and found, and which their object had prayed would emerge, approaches wider awareness now. The deception wakes to find itself struggling in competition with irrefutable analytical and documentary facts. Abraham smashed false idols in his father's workshop. But clay pots become brittle on their own and break after a time. |